Introduction

For my thesis, I wanted to write about objects. I have always been passionate about stories and in particular about the human history. Objects are a vehicle of stories, kind of fossils of civilisations.

They are never just tools, their study is not limited to their function. They carry within them our DNA. They reflect our economic system, our technological advances, our moral and cultural values. They are vectors of communication and emotion. They are a means of expression.

The first series of articles talks about language as a fundamental of our civilisation. Design is a form of language and it can be very different among cultures. Yet at the origin, there is a gesture. The second part is about the gesture of giving flowers. Their language, because although they are silent, they can tell us a lot. Their ephemeral nature which allows us to see the fragility and beauty of life in a few days. The madness they create by being a real consumer product, and finally the relationship between nature and culture.

An invitation to cultivate the useless, to cultivate flowers, to cultivate emotions.

A QUEST FOR HUMANITY

“usefulness of

useless knowledge”

« Just watch people hurrying busily through the streets. They seem preoccupied, look neither left nor right, but have their eyes fixed on the ground like dogs. They rush straight ahead, but always without looking where they are going, for they are mechanically covering a well-known route, mapped out in advance. It is exactly the same in all the great cities of the world. Modern, universal man is man in a hurry, he has no time, he is a prisoner of necessity, he does not understand that a thing need have no use; not does he understand that fundamentally it is the useful thing that can become a useless and overwhelming burden. If one cannot understand the usefulness of the useless and the uselessness of the useful, one cannot understand art; and a country in which art is not understood is a country of slaves and robots, a country of unhappy people who neither laugh nor smile, a country without mind or spirit; where there is no humor, where there is no laughter, there is anger and hatred. »

Eugène Ionesco, Notes et contre-notes, 1962.

In a world of utilitarianism, a hammer is worth more than a symphony, a knife more than a poem, a spanner more than a painting, because it is easy to understand the efficiency of a tool, but it is more difficult to understand what music, literature or art can be used for. In L'utilità dell'inutile , Nuccio Ordine writes in the conclusion of the introduction: "If we let what is useless and free perish, if we renounced the fertility of the useless, if we only listened to the siren song of the lure of gain, we would only end up forming a sick and memory-deprived community which, all distraught, would end up losing the meaning of life and the sense of its own identity/reality. And, once dried up by the desertification of the spirit we would then find it hard to imagine that the ignorant homo sapiens could maintain the role that he is supposed to play: to make humanity more human...”

Walker Evans, Beauties of the Common Tool 1955

Nuccio Ordino, L'utilità dell'inutile, 2013

Eugène Ionesco, Notes et contre-notes, 1962

COLLECTIVE IMAGINATION

about human being

What makes us human? What characterises us and will survive us?

The cognitive revolution has enabled Homo Sapiens to do very special things. From the years -70,000 to 30,000 BC, Homo Sapiens designed hunting instruments, boats, oil lamps or even needles to make clothes. It is documented that the first art objects and jewellery date from this period. The Lion Man is a statuette from the Stadel cave, which has been dated to around 32,000 BC. It consists of a human body and an animal head. animal. One of the first examples of art, it is also probably one of the first examples of religion and especially of the capacity of the human mind to invent things that do not really exist.

One of the characteristics of our language is that we can talk about these things that we have invented without ever having seen them. What is even more remarkable is that we can do this collectively. We can share ideas, build fictions together and believe in the same concepts. Two strangers can cooperate simply because they have common beliefs, such as the same nationality or the same religion. Yet there are no real gods, nations, laws, time units or money. These are simply concepts that we have invented. Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist, ranks the need to belong after physiological and security needs. We need to be part of a group and the concepts we invent allow us to create this feeling of belonging.

Unknown, Human with feline head, ca. 30,000–28,000 B.C.E

LANGAGES

![]()

what words can not say

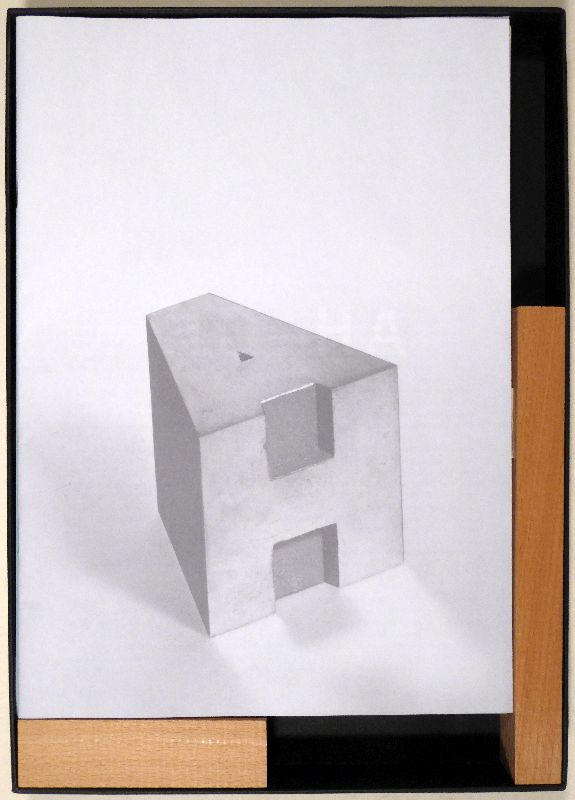

Although we have been designing objects for thousands of years, they are never just 'objects' - as Andrea Branzi will explain much better than I would, in the article dedicated to him - they are not just tools for carrying out everyday tasks. If we can ask why, the question of how is also very interesting. The materiality of an object, its design, its colour... are all clues to the civilisation that designed it. Typography is a very figurative example. In the design of a letter we can read the tone. It has an expressive value that resonates consciously and unconsciously in each of us. It can evoke an emotion; a typeface that follows the codes of handwriting gives a softer and more sensitive aspect. It can also evoke a language, a country or an era. Some typefaces try not to be associated with a period or a style and to be as neutral as possible, such as the grand papesse, Helvetica. Dal cucchiaio alla città, is a reworking of Max Bill's formula by the architect Ernesto Rogers. He talks about the relationship of Italian architects/designers with design: Able to create a spoon, a chair, a lamp and in the same breath, the same day a building. According to him, by observing a spoon very precisely, one could understand the company that designed it and visualise the type of city it would build. This language is therefore in everything around us, the typography of the newspaper we read, the bar chair where we read it, and even the drawn square where this café is set up.

Markus Raetz - Reproduction draw

Ernesto Rogers - Dal cucchiaio alla città

HUMANS AND STORIES

So is it the chicken or the egg?

Is it our culture that feeds our design, or our design that feeds our culture? If an object can have different forms, materialities, wear different costumes, there is already an element of subjectivity at its origin. If we were to limit ourselves to mere functionality, to the purest use, we would still not be able to achieve universality. Since the object is designed to meet a specific need of a target or an era. The collections of the Quai Branly show the lives of so many people by displaying their costumes, their crockery, their jewellery, their tools... We have the same faculties, we have similar vital needs yet our beliefs, our rituals, our destinies are very different and therefore our objects too. If we were transported to the future, what would we think, far from all our landmarks? Far from our heritage, our culture? Designing objects cannot be universal. A story is never an absolute truth when human observation is taken into account. What we see, we observe from our personal perspective, and it is very difficult to know if it is a shared truth. A good storyteller does not restrict himself to reality since reality is nothing more than the personal interpretation of what one sees or experiences.

Stanley Kubrick - 2001: A Space Odyssey - 1968